The National Certificate of Educational Achievement will be gone by 2030. File photo. Photo: 123rf

NCEA may be on the way out - but has it been delivering better jobs and income for the students who've completed it?

The system has been in place for more than 20 years, giving students level one to three qualifications as part of their high school education.

But with about 70 percent of school leavers going on to some form of tertiary education, does the fact of having NCEA level one, two or three improve a person's earning potential?

And how much?

Data indicates that it probably does - and the further you progress through the levels, the better.

Education Counts research, produced in 2020, showed that someone who left school in 2009 with no qualifications and who did not get any in the next nine years was earning nearly 40 percent less than those who got NCEA level one or equivalent.

They were earning nearly half what people with a level two qualification earned, 80 percent of what people earned who had University Entrance, and about a third of what someone earned who went on to finish a degree.

One in 10 people who left school in 2019 had no qualifications in 2018.

"For the small percentage of 2009 school leavers who got NCEA Level Three without UE, there was no significant earnings benefit, on average, over those who left with NCEA Level Two."

But the research noted it was a general trend, rather than a hard rule.

"One in three degree-holders, and around one in four doctorate-holders earned less than the median income of those with school qualifications.

"Similarly, not having qualifications doesn't guarantee low earnings. Around 30 percent of 30- to 34-year-olds with no qualifications earned more than the median income of people with a school qualification, and 20 percent earned more than the median income of those with a degree."

The research noted that the chances of working at all were higher with a Level Two qualification.

"Less than half of those with no school qualifications were employed nine years after leaving school. Non-employment accounts for much of the earnings disadvantage of this group, but even when comparing employed only, this group earns 15 percent to 30 percent less than any other group."

Figures provided to RNZ earlier by Education Minister Erica Stanford showed 13,496 Year 11s who attempted a full NCEA Level One programme last year fell short while 31,524 were successful.

Massey University Professor of management Jarrod Haar said educated people were more likely to have higher paying jobs in general.

But he said secondary qualifications did not need to be "fatal" to a person's career.

He said some people who dropped out of school were able to go back to study in their 20s very successfully and earn tertiary qualifications.

"Like most things once you get working you get work experience and pick up work-related skills anyway.

"It always used to be a funnel to identify who could go to uni but as we've become more universal in accepting people for study, which is probably a good thing, it's broadened the scope of whose who go to tertiary education anyway."

He said employers would adjust to whatever qualification system the government brought in.

Census data shows that for people with qualifications up to Level Three, the highest average income was earned by those in communications and media, who were getting an average $78,000. That was followed by science and technology at $77,000.

Hayley Pickard, founder of recruiter Fortitude Group said there was a global trend that the higher an individual's level of education the more access they had to job opportunities and further learning.

She said the changes proposed seemed positive.

"The renewed emphasis on core skills, particularly literacy and numeracy, also reflects this global shift toward ensuring that students meet key learning benchmarks before progressing.

"This focus may support improved long-term outcomes, both in employment and further education.

"At the same time, it's important to recognise that formal education isn't the only path to success. Many people excel through vocational pathways, entrepreneurship, or self-directed learning.

"Some of the most capable and successful individuals I know have achieved a great deal despite having left school early."

Brad Olsen, chief executive at Infometrics, said it was concerning that 43 percent of employers had told researchers they did not consider NCEA Level One when they were making a recruitment decision and more than 70 percent did not think it was a reliable measure of knowledge and skills.

If employers did not have confidence or understand it, it could mean people were hired who were not suitable or not at the level the employer was expecting.

"If as a business owner you are expecting a certain level of skills and you don't get that it can be frustrating and relationships between workers and bosses might be more fragile."

He said it was encouraging that it seemed the government planned to introduce a system with more focus on employability.

Secondary school qualifications played a big role in determining what students' next steps would be, Olsen said.

It would be a benefit if the system was able to encourage people down the right "pathway" more quickly, he said. "You don't want to dictate too early but you want to make sure they generally have some idea where they are going."

Olsen said it had seemed the NCEA system had a "uni or nothing" focus but it would be beneficial if students were encouraged into trades when it was appropriate, too.

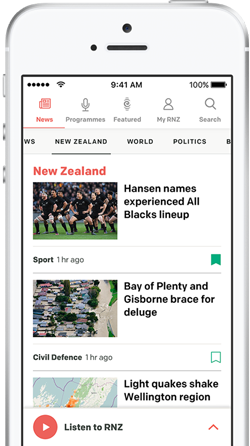

Sign up for Ngā Pitopito Kōrero, a daily newsletter curated by our editors and delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.