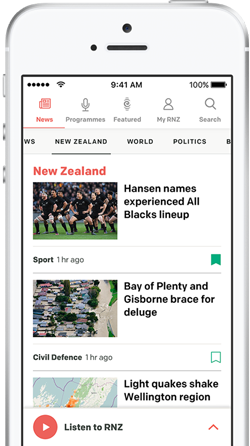

Mercury's Lexi Richards, Aimee McGregor and Matt Kedian on the roof of the new unit. Photo: RNZ / Libby Kirkby-McLeod

Mercury's Ngā Tamariki geothermal plant outside of Taupō will soon power up its fifth electricity generator.

It comes at a time when the government is leaning in to expanding geothermal potential.

RNZ was invited to tour the plant in its final stages of construction.

Standing on the roof of the new generator, Mercury's Major Geothermal Projects programme manager Aimee McGregor talked about its potential.

"This additional unit will generate enough electricity, which is 390GWh per year, to power all of [residential] Tauranga city," she said.

The Ministry for Business, Innovation, and Employment said geothermal generation was currently around 15 percent of New Zealand's electricity generation.

Geothermal generation works by tapping into the energy of water which is deep underground and therefore heated by the earth's hot molten rock core, sometimes to over 300 degrees Celsius.

Most of it in New Zealand is in the Taupo Volcanic Zone and McGregor said the country was lucky to have it.

"Ngā Tamariki field is quite a hot field, so there's certainly not a lot of places around the world that you can do this," she said.

Minister for Resources Shane Jones had made it clear the government expected more of geothermal.

He said New Zealand had been sold short in relation to affordable and secure sources of energy.

"And that drives me to expand geothermal options," he said.

The government's draft geothermal plan seeks to double the amount of geothermal energy produced for electricity and heating within 15 years.

Extra-hot fluids deep underground, called "supercritical", would help reach that goal, but they had not been successfully used anywhere in the world.

"If we have the ability and the technical know-how to create a new source of infinite energy, then we shouldn't shy away from it," Jones said, referring to the potential of supercritical geothermal.

Regardless, Jones said an enormous amount of progress in geothermal generation could occur with traditional geothermal processes which included 'flash' and 'binary'.

Mercury's Ngā Tamariki under construction Photo: Supplied / Mercury

Mercury used both processes, but Ngā Tamariki was a binary system where the geothermal fluid and steam was used to heat a secondary fluid which itself drove the turbine. The geothermal liquid was then returned to the ground once cooled to be reheated by the earth.

Mercury's head of generation strategy, Matt Kedian, said the government signalling its commitment to geothermal was important to the industry.

"I think it helps a lot. Probably the area where it provides the most assistance is when you start to come into consenting and getting more opportunity," he said.

Kedian thought geothermal generation was likely to increase.

"I think that's very likely, it's growing as a percentage at the moment," he said.

However, he thought the government's target was ambitious.

"That will take a lot of work to get there, but that's technically possible."

He said a key part of enabling future growth would be not losing talent.

"That will be our challenge, making sure we have got a funnel ... if we don't have exciting work [staff] will go find it somewhere else," said Kedian.

Amy McGregor said some internal changes to her team were aimed at keeping a pipeline of work for staff.

"My team will be used for developing more major geothermal programmes in the future, so obviously wanting to keep our team and our expertise engaged as soon as we roll off this one," she said.

Minister Jones said it was absolutely essential the country kept that skill base.

Though he might be in a war of words with the gentailers about electricity prices, he said he was 100 percent behind the workers bringing projects like this one online.

The fifth geothermal unit at Ngā Tamariki is on track to be reliably feeding the grid in 2026.

Sign up for Ngā Pitopito Kōrero, a daily newsletter curated by our editors and delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.