An international consultancy firm rated New Zealand's education system at the top of "fair", along with countries including Armenia and Greece, and behind Australia which was considered low in the "good" ranking. Photo: Supplied / Ministry of Education

How good is the school system? According to an internal Education Ministry document it's "fair" and we've been fooling ourselves that it's "great".

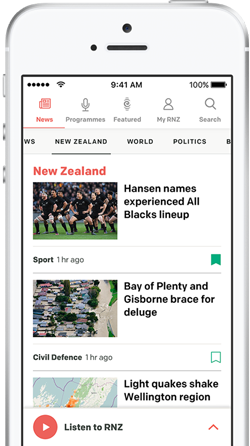

The document, sighted by RNZ and understood to date from 2023, also sets out three options for improving the system by specifying through the curriculum what teachers teach and how they teach it.

"Our data suggests that the New Zealand education system would be defined at the top of FAIR by McKinsey 2010 yet we have been behaving as if it is GREAT," it said.

The McKinsey reference appeared to be to a report by an international consultancy firm that rated education systems from "poor" to "excellent" based on performance in OECD tests between 2000 and 2010.

The report placed New Zealand at the top of "fair" along with countries including Armenia and Greece and behind Australia which was considered low in the "good" ranking.

Despite steadily declining scores, New Zealand ranked 10th in reading, 11th in science and 23rd in maths in the most recently published OECD Pisa tests of 15-year-olds.

The ministry's document said the introduction of a new curriculum in 2007 without sufficient support caused problems for schools.

"As we sought to shift from great to excellent, the 2007 curriculum went straight from a detailed curriculum to a very open curriculum. It did so however, without providing the supports needed to maintain and build on system coherence and capability," it said.

"Some schools with strong networks, resources, and accountabilities manage to perform well with minimal system supports but many of those carrying the weight of high needs and complex issues struggle. Teacher and learners both struggle."

The options for increasing the level of prescription in the curriculum ranged from a high degree practiced in "developing nations including Rwanda" to allowing a balance between the national curriculum and local decision-making similar to schools in Scotland and British Columbia.

The document said the most severe option was designed to move schools from poor to fair and the least severe from good to great.

The middle option, for moving school systems from fair to good, would mandate the school-level curriculum including what would be taught and when, though schools would retain some ability to localise their curriculum.

It said similar approaches were used in Australia and Alberta in Canada.

The document said under-prescription left decisions with schools and teachers "who do not always have the capacity or expertise to select appropriate content or approaches".

"This can contribute to learner under-achievement and exacerbate inequitable outcomes. The New Zealand curriculum environment shows evidence of under prescription in the highly variable quality of learning that students receive," it said.

The paper said over-prescription limited the ability of schools to respond to learners and contexts and to be innovative.

"Over time, over prescription may contribute to curriculum overcrowding and a focus on coverage rather than meaningful learning; this can contribute to poor learner outcomes," it said.

"Prescribed curricula are also liable to become outdated and require monitoring and support to stay up-to-date. A primary rationale for the design of the 2007 curriculum was to address over prescription in previous curricula."

The paper said over-prescription limited the ability of schools to respond to learners and contexts and to be innovative. Photo: RNZ / Mark Papalii

The ministry did not tell RNZ which of the options was being followed.

However, it said it had advised successive governments about the need to balance national direction with local flexibility.

"While high autonomy suits systems with uniformly strong practice and outcomes, New Zealand's variable, inconsistent, and inequitable performance-particularly for Māori, Pacific, disabled and low socio economic students means our current high autonomy settings are not justified," acting curriculum centre leader Pauline Cleaver said.

She said the previous government acted on the ministry's advice by starting to make the curriculum clearer about what all learners must know and do, and deciding to mandate a common practice model for how literacy and mathematics should be taught.

"The current minister has continued that trajectory, starting with issuing detailed curriculum and teaching practice expectations for English (Years 0-6), Mathematics & Statistics (Years 0-8), Te Reo Rangatira (Years 0-6) and Pāngarau (Years 0-8)."

Cleaver said the documents specified what students should learn over time, when and how key content must be taught, and how it should be assessed.

Auckland University professor of curriculum and pedagogy Stuart McNaughton said New Zealand's results in international tests were relatively good, but its ability to improve was only fair.

"In terms of the the quality judgement from the OECD in point of time and then over time, we're relatively good, relatively high quality," he said.

"But having said that, it is also true to say that we have had some declines in achievement and we need to recognise those overall declines in achievement which have in some of the assessments come from high performing students not performing quite as highly," he said.

"It is an unfair system and we have a real problem with our equity profile."

McNaughton agreed a greater level of prescription was required in the curriculum to improve New Zealand's school system, but he worried it might be going too far in places.

"It depends very much on the degree to which both content and teaching are prescribed because if you take it too far, you undermine the agency of the teacher, which is a great risk in a system that that prides itself on innovation and expertise, and the second risk is you've got to be really sure that you've got a good evidence-base for the content that you're providing," he said.

McNaughton said the recently-introduced primary school English curriculum over-prescribed how the youngest children should be taught to read because years of evidence showed different children needed different approaches.

Post Primary Teachers Association vice-president Kieran Gainsford said he agreed schools lost centrally-provided support in 2007.

He said teachers were hopeful it would be restored under the current reforms, but worried the ministry might not be able to provide it and teachers would be left to introduce the new curriculum on their own.

Principals Federation president Leanne Otene. Photo: Supplied

Principals Federation president Leanne Otene said years of "flip-flopping" education policies had damaged the school system.

"We have never been given an opportunity as a workforce to embed a curriculum and to really ensure that our workforce is confident and competent in the curriculum document and its teaching so that we can see improvement in student outcomes. We are just flip-flopping every time there's a change of government," she said.

Otene said the problem was happening again with more than 70 percent of teachers and principals telling a recent NZEI survey that curriculum change was happening too fast.

"At the moment that pace of change is overwhelming schools... Our principals who are leading teaching and learning for goodness sake, haven't even received any professional development yet and they are supposed to be leading these curriculum changes in their schools. So I would agree, we're not a world class education system," she said.

Sign up for Ngā Pitopito Kōrero, a daily newsletter curated by our editors and delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.